|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

By Charles Dhewa

While the profile of indigenous food has been rising over the past few years across Africa, policymakers are yet to direct policies and public spending to the majority of indigenous commodities. A lot of support continues to be directed at exotic commodities that are being threatened more by a changing climate.

Sweet potatoes as a substitute for wheat

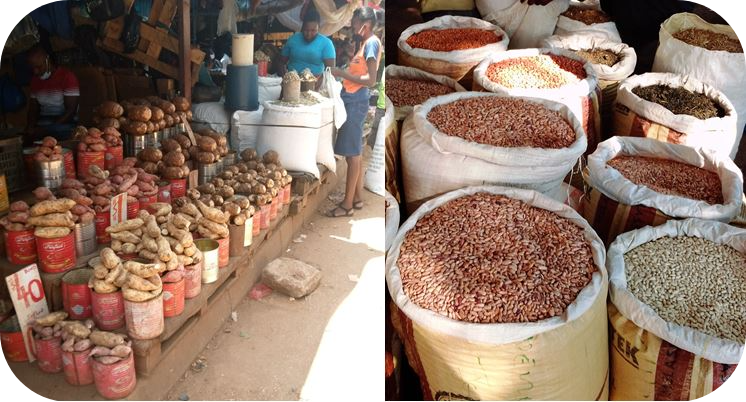

Although more farmers produce sweet potatoes than wheat, support continues to go towards wheat production in spite of the high cost of production compared to sweet potatoes. Except for Nigeria which has invested in substituting wheat flour with cassava in bread, most African countries are yet to focus on fully understanding their comparative advantages. For instance, in Zimbabwe at one time the majority of consumers eat thousands of tons of sweet potatoes but three months down the road the commodity is no longer available. This seriously disrupts consumption patterns.

Simply preserving sweet potato will make it available throughout the year. If 1000 tons of sweet potatoes are consumed within three months, producing and preserving the same quantity for 12 months translates to 4000 tons a year. This will guarantee good income for farmers and consistent nutrition for consumers. By not investing in preservation and all-year production, African countries are depriving farmers of reliable income and consumers of all-year-round nutrition. Instead of importing wheat each time, there is a looming bread shortage, why not produce and preserve enough sweet potatoes so that they substitute bread? More importantly, sweet potato production and preservation do not require foreign currency compared to wheat.

Small grains as a substitute for maize

African countries are always in a hurry to import maize as soon as there are signs of maize meal shortages. Why not take small grains as suitable substitutes for maize rather than complements? It is unfortunate that existing mechanization in Africa is not designed to produce, process, and preserve indigenous foods. Mechanizations is about exotic foods that are much fewer than diverse types of indigenous foods that do well in different microclimates. What are African universities and research institutes doing to promote indigenous foods as ideal substitutes for western food? Western consumers are coming more health-conscious and moving away from fast foods but African countries are still finding fast foods more fashionable.

Who is responsible for supporting the supply chains of our indigenous food systems?

There should be a government department responsible for raising the consciousness of Africans about the negative implications of junk food on people’s health and entire national economies. During gluts, economic losses for most indigenous food commodities range from 100 to 1000%. For instance, in Zimbabwe, a 50kg bag of sweet potatoes fetches USD8 during the harvesting period but during shortage periods, the same 50kg goes for USD80. This is about a 1000% price increase within three months. Such an economic loss has a huge negative impact on sweet potato farmers because there is no mechanism for preserving the commodity during gluts periods.

The same applies to small grains whose prices range between USD6-7 at harvest and rise three-fold to USD25 per 20 litre tin during shortage periods. Farmers suffer economic losses during gluts due to lack of preservation, processing, and warehousing facilities. This also affects African indigenous wild fruits that are only in the market for a month or two, during which period they are in abundance and fetch very low prices.

Need for a government department responsible for indigenous foods

If indigenous food is going to receive the policy attention it deserves, each African country should set up a ministry in charge of indigenous foods including forest products such as medicinal herbs on which the majority depend. Such a ministry will support a transformative shift from production to marketing and preservation of indigenous foods as well as product development. Currently, a typical ministry of industry and commerce in any African country focuses on the commercialization and industrialization of exotic foods. If not supporting corporates, that ministry is focusing on importation of exotic commodities that do not meet the needs of the majority of African consumers. Efforts to improve food standards only focus on industrial food systems, not local markets from where the majority get their food. When commodities like peas are rejected on the export market that is when they find their way to the domestic market.

More importantly, African countries continue to lack value addition nodes where, for instance, at the end of a supply chain, sweet potato will have gained four to five times the value of raw sweet potato. A lot of research has gone into Irish potato with no equivalent attention going to sweet potato and other tubers that can easily compete with Irish potato, if not substitute it. If African universities and research institutes were really committed to developing indigenous foods, all African mass markets would be centres of research and development where diverse foods are researched, tested, developed, and promoted.