By Farai Chirimumimba

The world is used to trailing behind Zimbabwean political drama. The Government of National Unity (GNU) helped bring Zimbabwe the best years since the the turn of the century, when it was the breadbasket of Africa.

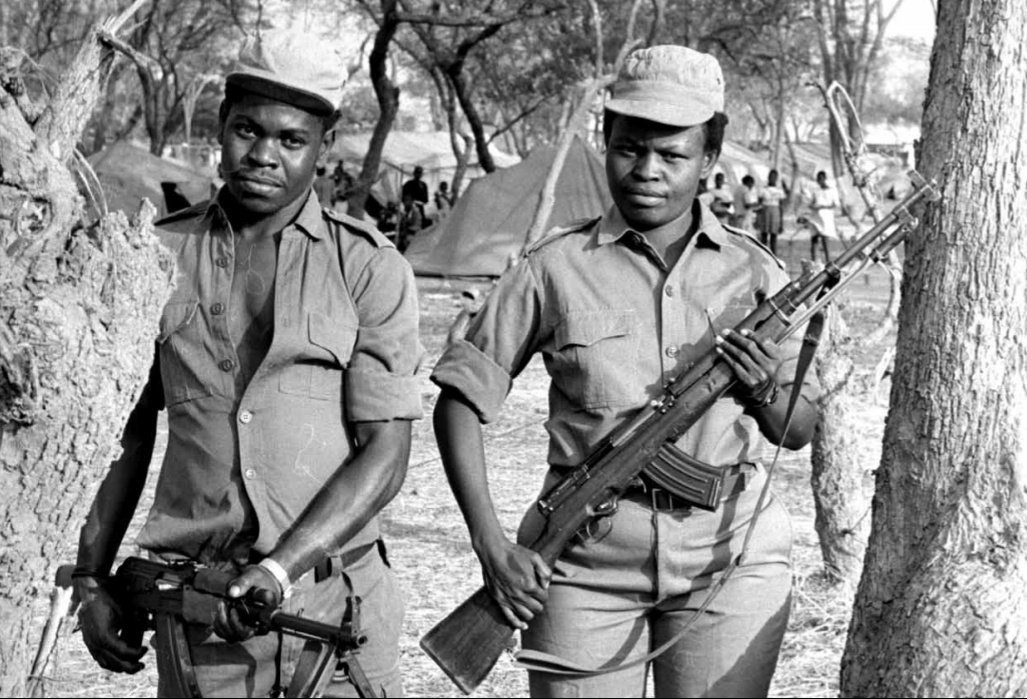

Those heydays had been followed by nearly two decades of decline and political instability. Between 2000 and 2019 Zimbabwe saw six disputed general elections, one most visible military coup, and at least four post-election violence incidences.

In the worst of those in 2008 over 200 mostly opposition MDC-T supporters were reportedly killed. In the last of these on August 1, 2018 at least six people were gunned down by either the police or the army as concluded by the Monhlante Commission.

Further, over 20 people also died during the fuel riots in January 2019. The small landlocked country is in shambles. Its economy is stagnant: on current forecasts it will finish the year with a negative average growth rate (-5.2 % according to IMF) since 2009 in Southern Africa— behind even Cyclone Idai hardest hit Mozambique.

On April 18th Zimbabwe will celebrate the 39th anniversary of its independence. But the festivities will be muted by frustration with its performance.

The Zimbabwean economy should by rights be booming. The landlocked country is neighbour to South Africa, Africa’s third biggest market, with which it shares dialect. It is on the shipping route from Durban, South Africa to several Africa countries, and has a spacious natural wonder of the world, Victoria Falls. It is generally politically stable, without the visible ethnic tensions that have riven other African nations.

Zimbabwe has reasons for its plodding growth of late. Agriculture, which is the backbone of the economy and employs many of the Zimbabweans, has dipped with the chaotic land reform at the turn of the century. And the market for tobacco and gold, its main export goods, has been rockier than for other commodities. However, the country’s economy was stagnant long before the the accelerated land reform. In real terms Zimbabweans are no richer today than they were in the early 1980s. And most of the countries enduring problems, like its public finances, are home-made.

Zimbabwe has run more back to back fiscal deficits in 39 years of independence. Few people pay taxes: the middle class is small, the informal economy big, and enforcement chilled-out especially for the so called “big fish”. It is not clear how many registered firms contribute tax. The government has steadily dished out waivers to favoured foreign nationals with reports of some Chinese firms getting generous tax breaks.

Expansionary fiscal policy that led to back to back fiscal deficit; rising vulnerability and poverty because of unfavourable weather conditions and financial shocks; and acute foreign currency shortages affecting demand and supply. Lacking sufficient revenue, Zimbabwe has financed public spending by borrowing. Years of accumulated deficits, no bail-out, and punishing interest rates have swollen the national debt to US$ 16.9 billion by October 2018. Servicing the burden may require real austerity measures and punitive roll overs.

The government has further hurt the economy by unwise intervention in the market. For example its firm grip on foreign currency allocation has suffocated local firms (never mind the rhetoric of liberalisation). That has limited job growth for the young people.

The private sector has also been shackled by bureaucracy. Filing taxes

requires several steps and many hours a year, twice as long as in Rwanda. Importing few goods can take a whole day at the border. Manufacturers complain about electricity, which takes up to three months to get connected.

Professor Mtuli Ncube, who became finance minister in September 2018, is cautiously trying to broaden taxation. Despite furious complaints, he extended intermediary mobile transfer tax last year to transfers over RTGS$ 10 billion. The IMF may require the government to end some quasi-fiscal programmes that are increasing borrowing.

There are tentative signs that security, a big cost to business, may be improving. Many companies spend over RTGS $100,000 a year on guards. Although the country’s armed robbery problem maybe getting worse, several armed robbery gangs were arrested over the years. The murder rate is also now creeping up.

The country will need a political makeover to improve its policies. Both main political parties pander to interest groups whose votes are controlled by self-fish strongmen. Members of parliament tame plump in a partisan manner because of the whipping system. That means policy proposals have little effect through non-partisan debate.