|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

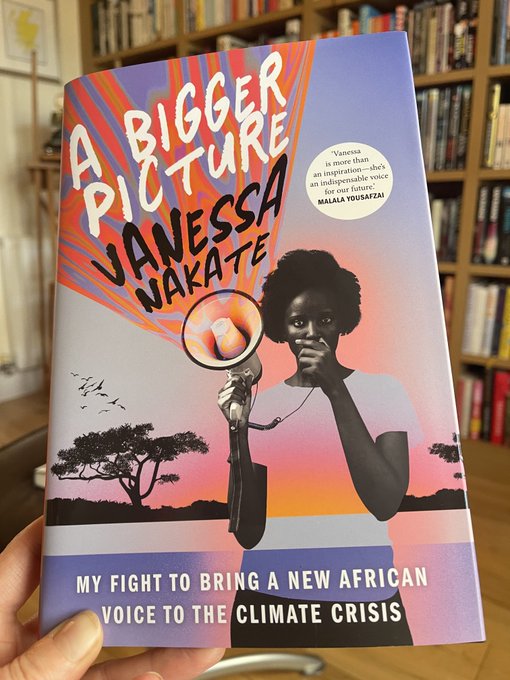

Vanessa Nakate, a Ugandan climate activist, emerged as one of the most prominent youth voices at COP26 in Glasgow. “Prove us wrong,” was her message to delegates at the climate talks, which entered their final day on Friday, as fears grew that countries would fail to convert ambition into an agreement.

Activists and delegates from developing countries, including many African nations, have strained to define the debate as one of climate justice. One of the major sticking points is the doubling of funds to help poorer countries deal with climate impacts. In the past, richer nations like the US have resisted efforts to ramp up climate finance.

At the latest round of talks, some of the most vulnerable countries are seeking funds not just for adapting to the future impacts of climate change but also compensation for “loss and damage” that has already occurred.

Civil society representatives from African nations consistently drew attention to deepening hunger and food insecurity. Three out of the ten countries facing the greatest threat from climate change are in Africa, with Madagascar ranking fourth, Kenya placed seventh and Rwanda eighth. Madagascar is currently in the grip of a drought the UN warned could trigger the first climate change-induced famine.

In 2015, when countries signed the landmark Paris agreement to curb greenhouse gas emissions, the African nation’s per capita emissions stood at 0.12 tons/person, compared to 16 tons/person for the US.

The US has historically emitted the most greenhouse gases. In recent decades, though, China’s annual emissions have swelled, placing it first among polluters, with the US second, the EU, and India coming next. China, India and Saudi Arabia have, as of Thursday, opposed the entire section of the COP26 final agreement on climate change mitigation; that section contains all of the agreement’s language around reducing emissions.

“This rise in temperature will only be stopped if there is also a change in consumption and production patterns in the so-called polluting countries,” Madagascar’s environment minister, Baomiavotse Vahinala Raharinirina, told AFP. Raharinirina said a “psychological distance” prevented people from grasping the harshest realities of the climate crisis.

At a session organized by the British philanthropy Campaign for Female Education (CEMFED) on Tuesday, delegates from countries in Sub-Saharan Africa attempted to narrow this gap.

“Climate change means hunger and scarcity in our communities,” Fiona Mavhinga said of her native Zimbabwe.

Mavhinga, a lawyer by training, is the co-founder of the Camfed Association (CAMA), a network of African women leaders.

Welsh philanthropist Ann Cotton formed CAMFED in 1993 to support women’s education in marginalized communities in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2013, the NGO started training women as Agriculture Guides or champions of climate-smart agriculture.

At Tuesday’s discussion, other panelists also drew a clear link between climate change, food insecurity, and poor education access for girls. They were speaking from experience, narrating mirroring accounts of living with grandparents or relatives who worked as smallholder farmers.

“Agriculture is life in my community. People depend on land for their livelihood,” Forget Shareka, an entrepreneur and CAMA member from Zimbabwe, said. “When weather patterns change, they affect crop production.” High temperatures and droughts cause crop failures, she said.

Given the opportunity to continue her education thanks to CAMFED’s support, Shareka decided to pursue a bachelor’s degree in agriculture science. She went on to co-found an enterprise that aims to reduce post-harvest losses.

It was the kind of story Nakate said was missing from the broader narrative about climate change.

“We have seen how continuously activists from the global south, who are speaking up from the most affected communities — their voices are not being platformed,” Nakate told radio network NPR of COP26.

“Their voices are not being amplified. Their stories are being erased.”

The 24-year-old is no stranger to erasure. She attended the World Economic Forum in Davos along with white climate campaigners, including Greta Thunberg, last year and was infamously cropped out of an Associated Press photo, provoking allegations of racism.

The climate talks have come under scrutiny for poor representation from African nations, which are most vulnerable to climate impacts. Lack of funding, COVID-19 restrictions, changing travel requirements, and Britain’s immigration system limited the participation of delegates from some countries. An estimated two-thirds of civil society organizations who usually send representatives to COP have not sent them to Glasgow this year, possibly making COP26 the whitest and most privileged climate summit ever, according to activists.

Malidadi Langa, who works in his communities living around Kasungu National Park in Malawi, said he couldn’t secure funding despite wanting to go. “Major decisions that affect the natural resources, whether it’s wildlife, forestry, are made at a higher level at international fora,” he said. “but they have a huge impact on local communities.”

Langa said mostly international NGOs, backed by big-ticket funders, get to go to events like COP. “They will be speaking on behalf of my village, which we do not like,” he said. “They end up misrepresenting our issues.”

His concerns also centered on the poor soils and erratic rains that lead to crop failures. “Farmers get very little for their sweat,” Malidadi said. “These are people who are hardworking, but climate change and the soils are failing them.”

Millions of people go hungry in the region every year, and the changing climate has only made matters worse. “Unfortunately, these are the things that those who are making decisions around climate change do not see,” he said.

Source: Mongabay